Unsodo - A Talk with the President

Regarding the fine shin-hanga woodblock prints by Unsodo Publisher, many of their seals and some artists' information is already

accessible

here at this website. Now however (March 2002), for the very first time, I had the opportunity to meet with

Mr. Teiichi Yamada, President of Unsodo in Kyoto.

Unsodo is a publishing house of long tradition. Founded in 1891 (Meiji 24)

- not in 1887

as mentioned in Merritt & Yamada by Naosaburo Yamada - it is still a family enterprise and run

by the third generation by Teiichi Yamada, the grandson of the founder. This

tradition most likely is to continue, because the son of the present President,

young Mr. Yamada, is also himself active in the family business.

|

|

|

|

A view inside the Unsodo Shop in Teramachi

/ Kyoto

|

Unsodo of Kyoto is located in the traditional, beautiful Teramachi District

in Kyoto, not far from the Nijo Palace. In a small street, which suddenly opens

into a wide space in front of the shop, we see already from the distance the

black Unsodo signboard with its characteristic "kanji" lettering. The store itself is spacy, with

many prints handsomely displayed upon its walls. Many more prints are visible within the glass vitrins. Shoppers, and

the woodblock print collectors among them, can easily spend many hours here. Upstairs is a another small

gallery where still more prints are displayed, amoung them a range of flower prints, that

have found entry into a catalogue of the famous French fashion house Hermes. Also on

display is a set of brushes and "baren," shown to demonstrate the basic

tools of the woodblock printing process.

An old signboard of the store has survived the

War and is also on display. Unusual for us - at least in Japan - is the writing in the typical French "Art Noveau"

style--where East meets West and West meets East. The three digit telephone

number "290," mentioned again in Japanese writing in the bottom line from right to

left, tells us how old this signboard really is. And note, Unsodo sees themselves curiously as being

"booksellers!"

|

|

A small office is at the end of the showroom, where several employees take

care of the daily business, which nowadays is concentrating still more on books and

their decorations than on the selling of woodblock prints.

But the true treasure certainly is certainly not just the inventory of prints within the shop, but rather, lays hidden

in the darkness of a separate building nearby. Adjacent to the Unsodo shop and not visible from the

street, is a typical Japanese "kura," a stone-built warehouse, with

small iron clad windows only in the second floor. Such "kura" (fire-safe storage rooms) date at least to as early as Edo era Japan (pre-1868), when Japan's cities were frequently ravaged by fires--and so, shopowners and homeowners typically used them to store their valuables. Here, secured by a massive steel door, this

building is the storage for many thousands of woodblocks - books, ukiyoe, flower

prints and shin-hanga!!

|

|

Mr. Yamada was incredibly gracious to grant me access to this specially guarded building. Surprised by

the darkness - the wooden blocks almost turned into deep black after many decades

of storage - and impressed by the sheer amount of woodblocks, I moved between the heavy shelves

laden with hundreds and hundreds of these carved blocks.

The traditional construction of the "kura," combined

with the heavy volumn of woodblocks, keeps both temperature

and humidity almost constant throughout the year - a must for

woodblocks which would otherwise warp and change in their dimensions.

To the right: Mr. Yamada amidst of his "treasures".

|

|

Most of the blocks were kept together as a complete "sets," often wrapped

into newspapers (the date of the newspaper easily indicates when the last reprinting

had occured) and bound together. On top of many such bundled sets is often seen the particular

print image put there for their immediate identification; other block sets are simply identified

by a lable, see here in the right image, "ringo = apple", or Cyclamen, both in Japanese

characters.

Several blocks observed were carved on both sides to save material, and the remaining pigments also made it clear

that occasionally two different pigments got applied onto the same block - provided

there was some physical distance between the designs cut.

To keep track of such an impressively large inventory, which was accumulated over a period that

covers more than a whole century, is certainly a challenging task. Right now, it is my

feeling that the people involved simply remember where a specific set of blocks

rests in the storage.

Found among the blocks also rests the entire original blocks of the Hokusai "Manga,"

which got reprinted as a complete 15-volume set by Shinmi Saburo on behalf

of Unsodo in 1961.

The primary interest of my visit was, of course, to learn more about the shin-hanga artists

Kasamatsu Shiro (1898 -1991) and Asano Takeji (1900 - 1999). Of the former, Kasamatsu himself had 102 prints published by

Unsodo over an eight-year period spanning from 1952 to 1960, before Kasamatsu himself then turned completely

to

the "sosaku" philosophy of carving, printing and publishing prints completely

through himself, influenced by the early death of his second son (aged 20) in

1955. The collaboration of Unsodo with Asano, about whose scope of works

less is known so far, began in 1949 and continued for a couple of years.

Somewhat surprisingly, Unsodo's stock of prints of both these artists is now rather limited, clearly an

indication of past good sales. The sought-after first editions of high quality are now

virtually all gone. One should also keep in mind that in addition to sales done by Kyoto Unsodo, a lot of additional business

is done via Unsodo's Tokyo branch. From both artists, Unsodo published only works

in the tradional "oban" format--they did not publish any "chuban"

size (half sheet) prints or postcards. The primary printer was Shinmi Saburo (sometimes incorrectly

pronounced "Niimi," because the kanji of his name allows both possibilities).

Shinmi, born 1912 in Shizuoka Prefecture, learned printing around 1930 from

his uncle Yohei Shinmi and remained active until around 1996.

|

|

Then forwards (since approximately 1996), a young new printer named Toda now acts for Unsodo for the reprints of Kasamatsu

and Asano. Note however, it cannot be excluded that some prints although made by Toda, still (incorrectly) show

the

"koma" bearing Shinmi's name (as printer) within the prints' left margin. One of the first later editions to correctly show Toda's

printer's seal

is Kasamatsu's famous design of the "Nikko Kegon Falls." This new edition of 50

sheets is printed on paper with a high "mica" content, adding a nice shine to

the print's surface.

Of course, it is known that the EARLIEST versions of the prints of both Kasamatsu and Asano bear a "key-block" printed date in

Japanese writing within their lower left margins, whereas later editions do not. At this point Mr. Yamada revealed an amazing discovery--he

explained that immediately upon completition of each prints' very first edition (which comprised

usually 100 sheets) the "key-block's" carved date then got cut from the block. Hence, ALL later reprints--although

to a great extend still printed during the lifetime of the artists--are therefore undated. The significance of this revelation is that such dated "first edition" prints are much more scarce than previously believed.

|

Additionally, it is also observed that occasionally "first editions" and "later editions" show

even further differences than simply the "date-block" of the first version.

For example, here we see in the leftside image a first version of Kasamatsu's "Spring

at the Moat," while to the rightside is a later edition. Apart from

the different color scheme of the background wall and the wave

pattern - the early version tends to be warmer - and a different

"bokashi", we notice, that the printer added in the

later (right) version a red forehead into the reflection of the middle

swan, which does not exist in the early version. Also, the "seals"

are different. Compare the large artist's "seal" in the lower right

image corner of the first edition with the "standard"

Kasamatsu "seal/signature" combination in the right upper image

corner of the late edition.

|

|

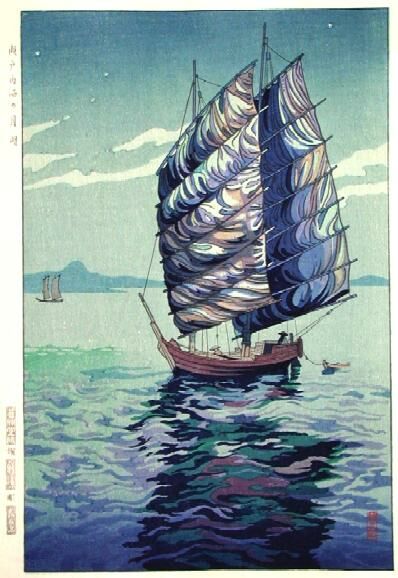

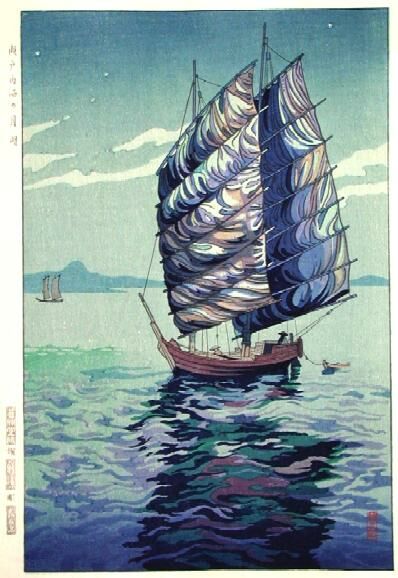

Another discovery--according to Mr. Yamada my small catalogue raisonnee of Kasamatsu's works (titled "Shiro Kasamatsu--The Complete Woodblock Prints") which

mentions all his prints published by Unsodo, probably even includes one print too many: the print #U-90,

"Moonlight over the Inland Sea," 1958, bears a seal "Shintaro". Although

this print is listed by Unsodo itself as #SK-31 in their official Kasamatsu Catalogue, Mr. Yamada

believes that the artist is actually Shintaro Okazaki and that they for reasons

of convenience - since only one print of this artist was in question and the style

and character fit very well into the Kasamatsu prints - they simply treated this

print as "a Kasamatsu."

|

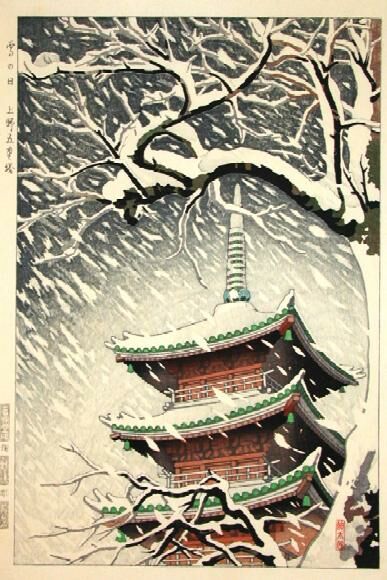

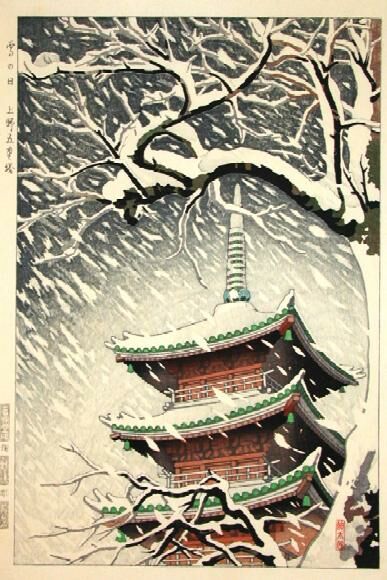

This author, however, knows of at least one other print

(carved by Okura, printed by Shinmi) published by Unsodo which bears

the red boxed “Shintaro” artist’s seal. This nicely done view of a pagoda in snowy weather is, however, in its entire composition

and workmanship substantially different from #U-90--therefore, both images

do not seem to come from the same artist as their “handwriting” is

too different. Certainly more research is required to come

up with a conclusion whether #U-90 really may be attributed to Shintaro

Okazaki and not to Shiro Kasamatsu.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

#U-90, "Moonlight over the Inland Sea"

|

( "Yuki no Hi - Ueno goju no to")

"Snowy Day - Five-story Pagoda at Ueno"

|

"Shintaro"

|

"Shintaro"

|

As an aside--another print, "Ikebana" (#U-102), which had not previously been precisely dated in the "Complete Kasamatsu" book has just recently been discovered in a margin-dated state. By reading its "kanji" date ("Showa niju nana nen saku"), we now know with certainly that "Ikebana" was created in 1952 and not merely "around 1960" as Unsodo of Tokyo had surmised when asked about this print several years ago.

The prints #U-42 and #U-43 ("Naruko Hot Springs," 1954) are according to an exhibition at the Yamanashi Prefecturial

Museum in 1996 as being two different versions - a light and a dark one. However, Mr. Yamada cannot remember that

different versions were done on purpose--rather, he guesses that most probably two color variants (caused by different batches of the print) were mistakenly taken to be different versions.

All in all, the meeting with Mr. Yamada was both very pleasant

and most

interesting--but, of course, too short. Certainly there will be a follow

up!!

To the right: The author with Mr. Yamada inside the

Kyoto Unsodo shop.

|

|

© Copyright Dr. Andreas Grund (with editing by Thomas Crossland) 2002