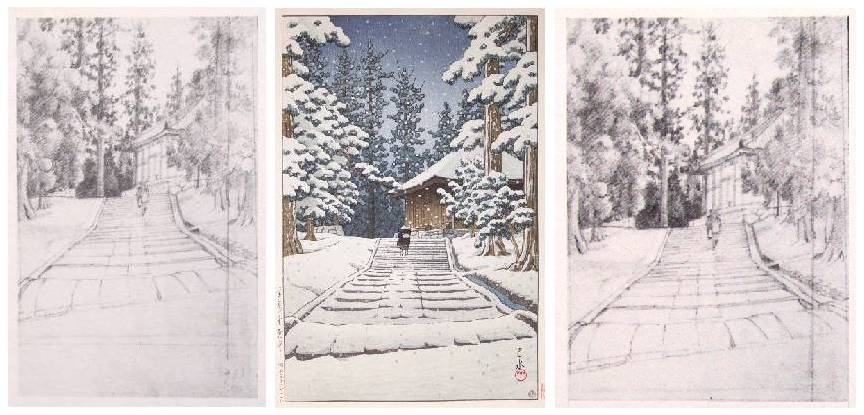

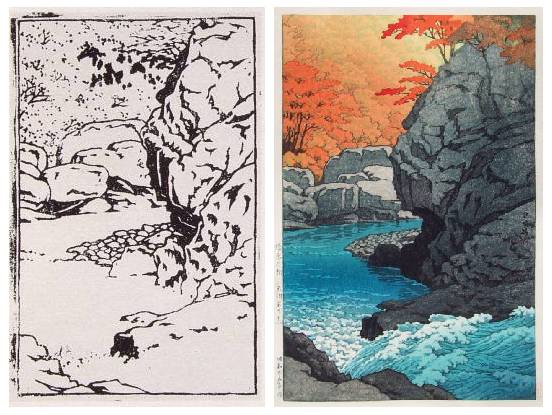

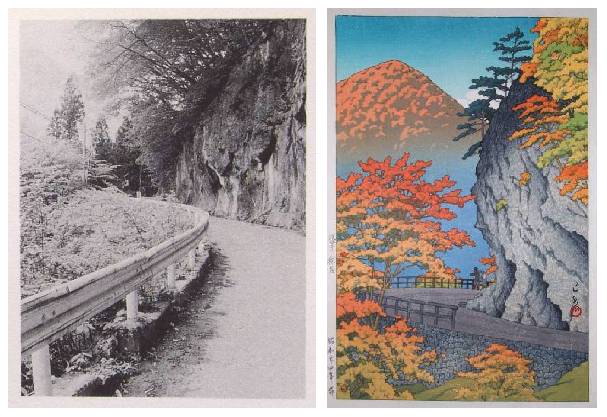

Without doubt, being able to view several of the "preparatory sketches" made at various locations by Hasui affords to the viewer some insights into the development of an original black and white pencil sketch into an eventual full-color woodblock print. The study of these various black and white sketches thusly gives us a bit of a “window” through which we can better view the artistic process of print development. And, if we are lucky enough ourselves to actually hold one of these same color woodblocks in our own personal collections, then the insights gained and comparisons made from viewing the earlier sketch can be even more meaningful.

Literature sources used in preparation of this article include:

"Kawase Hasui -- The Otaku/Yamanashi Exhibition" Tokyo, 1990

“The New Wave – Twentieth-century Japanese Prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection,” Amy Reigle Stephens, Bamboo Publishing, London, 1993, ISBN 1-870076-19-2

"Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, 1900-1975," Helen Merritt & Nanako Yamada, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1992, ISBN 0-8248-1732X