Additional Deluxe Printing Techniques

Introduction

Always delightful is the first handling of a woodblock when one is pleasantly surprised to discover the presence of various unexpected deluxe printing techniques. In addition to "gauffrage" (or embossing) which is discussed in an earlier article titled "Deluxe Printing Techniques--Gauffrage", these advanced techniques can include "bokashi," metallic pigments, lacquer, burnishing, "baren sujizuri," mica, and visible woodgrain. Each of these seven different print-enhancing techniques will now be explained and illustrated below.

Gauffrage detail, "Tama" c1924 Shotei print.

Without doubt, a few words of well-deserved praise should now be made to acknowledge the often unrecognized or under-appreciated efforts of the carvers and the printers that bring to life the artistic visions of the many Japanese artists whose prints we avidly and enthusiastically collect. It is understandably perhaps that it is the Japanese artists alone upon whom we heap our praise and adulation--however the enlightened collector will soon realize that the two other members of this "artistic triangle" also deserve considerable praise and recognition.

The Carver

It is, after all, through the highly skilled and disciplined efforts of the artisan carver that an artist's initial black and white "sketch" begins the process of becoming a multi-copy print. In an effort that is typically orchestrated by the publisher, the printer is entrusted with the artist's original "sumi" ink sketch which he then glues face down onto a fine cherrywood plank, from which he laboriously carves the print's "key-block." From this "key-block" then, a handful of "hanshita" are then printed which then become the "templates" which are similarly glued onto still more cherrywood planks and then differently carved to produce the additional perhaps dozen or more colored blocks. It is said that the skills required to become such an artisan carver can involve an apprenticeship exceeding 10 years, and that the carving of a complete set of blocks needed for the printing of a single woodblock image can take as long as a full year. A more detailed and illustrated discussion of this process can be found via this article titled ""Hanshita," or Black Ink "Key-block" Outlines.")

The Printer

The final member of this three-person team--and the person of whose efforts are the focus of this article--is the artisan printer. Similar to the apprenticeship served by the carver, the length of training can often approach 10 years. However, unlike the carver, the printer has considerable freedom and artistic license to vary the outcome of the final print's appearance. Certainly not all finished prints are identical; and even greater variation is often observable between successive production runs. Obvious to the careful observer of Japanese prints are the artistic efforts of the printer, for it is through is careful and skillful manipulation of colors and by other techniques that the artist's initial vision truly comes to life before our eyes.

"Bokashi" (Gradation of Colors)

Perhaps the most widely observed advanced printing technique is "bokashi", or the skillful gradation of a print's colors. Of course, the reader should certainly realize that EACH color that is printed in any Japanese woodblock is done so via a cherry woodblock that is uniquely carved and then inked to print that specific color. However, rather than simply applying ink uniformly to the entire surface of the woodblock's printing surface, the printer can instead oftentimes achieve a more pleasing effect by varying the color shading through his inking of the woodblock's surface. By wiping, shading, and varying the amount of the ink that is applied to the woodblock surface, the skillful printer can achieve an astonishingly wide variety of color intensity seen within a print.

This "bokashi" technique was widely used even during many of the prints of the mid-1800's; consider, for example, the typical "blue-band" seen across the top edges of many of Hiroshige's landscape prints, or the similar "red-band" seen across many of these same print's horizons.

This technique is most easily observed in the "wider areas" of a print's surface, where larger un-carved areas of the woodblock easily allow this color manipulation--a wide "sky area," for example. But "bokashi" can be equally effective even when applied to much smaller areas--as for example, the pink shading seen to many a "bijin-ga's" face. Without a doubt, one of the most widely used and most artistically variable of all printing techniques is the printer's skillful use of "bokashi" shading.

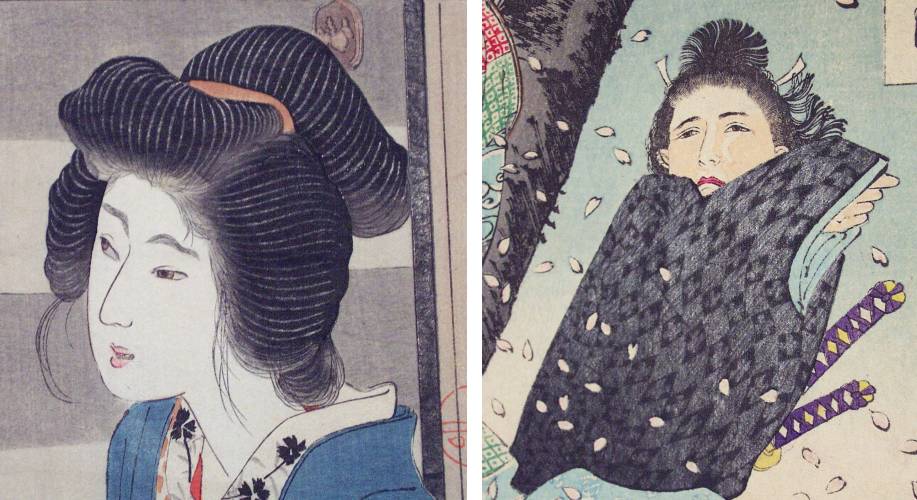

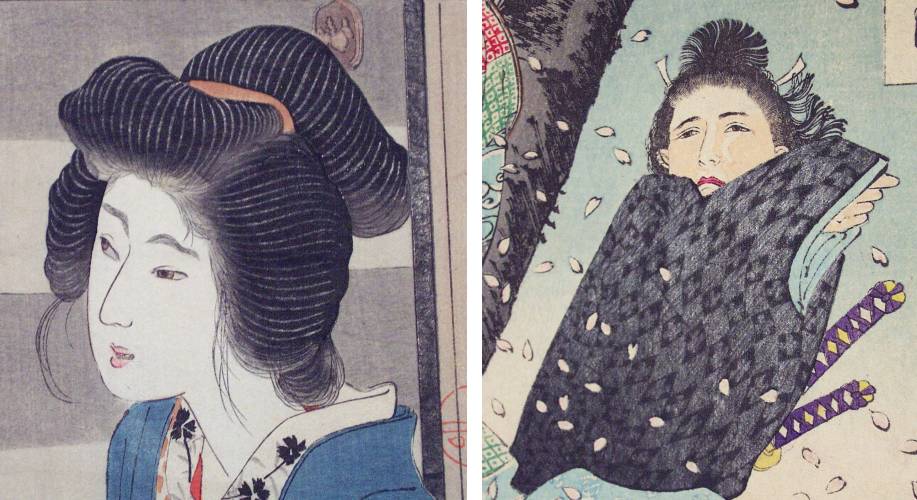

Bokashi to "kabuki" face, detail c1893 Toshihide print. Bokashi to carp, c1930 Koson.

Metallic Pigments

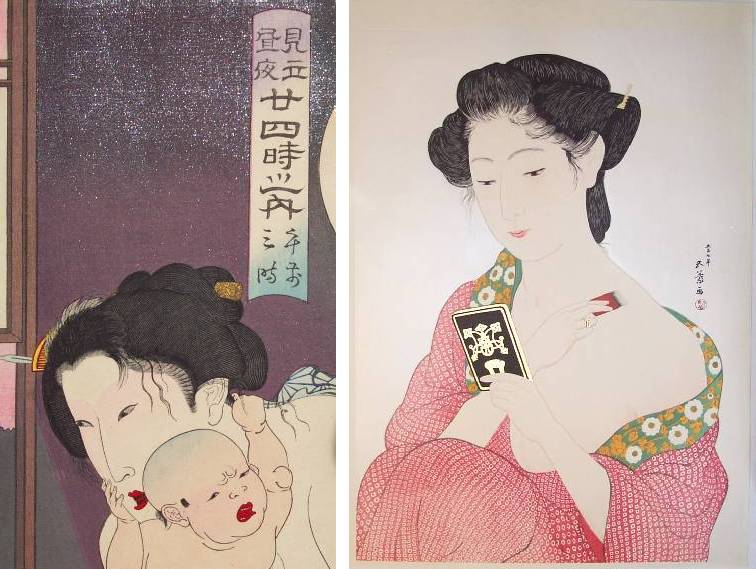

A second printing technique that is certainly delightfully encountered is the printer's use of metallic pigments. Commonly encountered in the printing of smaller "surimono" prints (privately commissioned, small gift editions) of the early 1800's was the use of gold, silver, and other metallic pigments. Although less widely seen in the prints of the mid-1800's, the application of these metallic pigments increased during the later Meiji period (1868 to 1912) and can often also be seen in "bijin-ga" prints of the later shin hanga period (generally post-1910). Their application is also commonly encountered in the printing of "shunga" (erotic) prints of all eras.

Oftentimes these gold and silver pigments are used not only to highlight a beauty's hairpins or other jewelry, but also often to embellish intricate designs seen with a kimono's pattern. Two such examples are seen below.

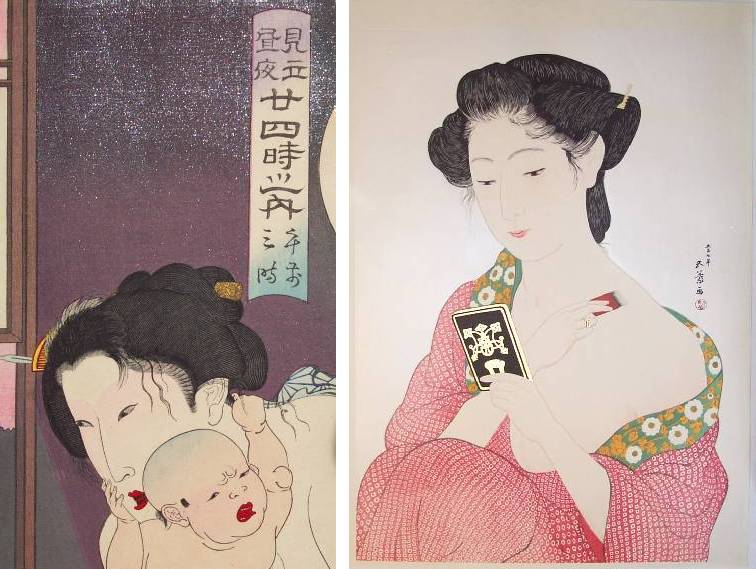

Metallic pigments, Toshiaki c1880's print. Metallic pigments, detail of "shunga" c1840's attr. Utamaro.

Lacquer

Lacquer (typically black) is another technique used by the printer to bring emphasis and a life-life appearance to certain areas of a print. Shiny black lacquer is especially prevalent during the prints of mid to late-Meiji Japan (c1880-96) where it was widely used to convincingly produce the shiny black surfaces of black belts, black shoes, and horse's black hooves. For this reason, lacquer seems especially common to the many Sino-Japanese "war prints" of 1895-96. Lacquer is, of course, achieved via the typical printing process, where it is applied to the woodblock's surface and then transferred to the print's surface; it can often be differentiated from burnishing (which follows) due to its "thicker," more "raised" appearance.

Lacquer highlights to crow's feathers, detail c1910 Koson image.

Burnishing

Burnishing is another technique which can be used to by the Japanese printer to produce areas of shiny blackness. However, unlike the application of lacquer which is discussed above, burnishing is achieved by a different two-step process. First, an application of non-shiny black is applied to the print's surface. Then, once dried, this dull black printed surface is then "shined up" by the repeated dry-rubbing of this same surface (again placed over the raised area woodblock) with a smooth bone or piece of ivory. The result is a moderately "shiny area" which is a result of this "polishing" technique.

Here, the reader can again see that not all printing techniques are achieved soly via the application of pigments to the paper's surface. Again, like "gauffrage" ("karazuri"), this burnishing technique is achieved by simply the application of much downward pressure over a DRY woodblock. Additionally, via burnishing, certain very interesting "black-on-black" patterns can be achieved, as illustrated below.

Burnished hair, c1910 Hirezaki "kuchi-e." Burnished "diamond-pattern" c1889 Yoshitoshi "100 Moons."

Circular Baren Traces ("baren sujizuri")

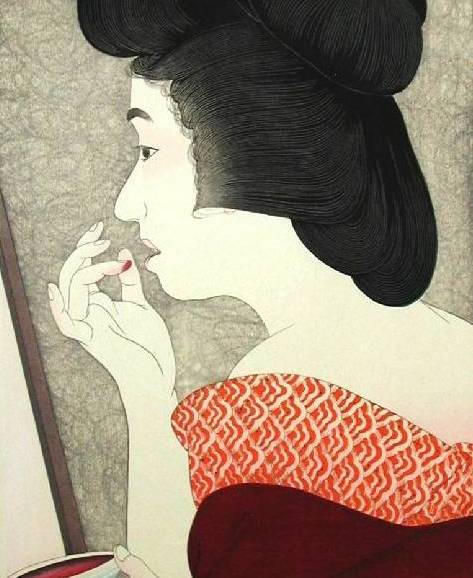

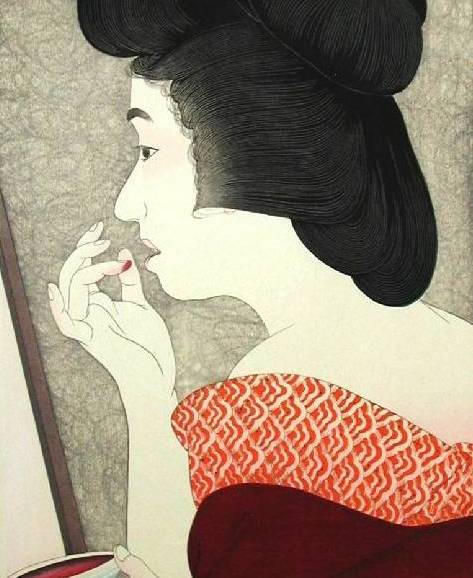

Another special effect that can be achieved by the printer is the appearance of having added "texture" or variation to the print's surface via the technique called "baren sujizuri,' or "circular baren traces" printing. This technique is said to have first been used in Ito Shinsui's 1916 print, "Before the Mirror" (or "Red Geisha") where publisher Watanabe urged his printer to experiment with the addition of "texture" by holding the "baren" tool on its edge rather than flat as was always previously done. The result was a pleasing random circular pattern that gives the print's background added interest.

Since the printing of Ito's "Red Geisha," these circular baren tracings have been used very effectively to produce the appearance of texture to rock walls, paved surfaces, and other background areas.

"Baren sujizuri" background to c1930 Kotondo "bijin-ga" print, "Rogue."

Mica

Another delightful technique that can be used by the printer is the application of "mica" to a print's surface. To impart this shimmering effect to the print's surface, the printer first applies his background coating of colored pigment mixed with some rice-paste, then sprinkles over this still-tacky surface a dusting of mica. This technique easily dates to common usage during the late Edo prints (pre-1868) where many of the female portraits done by Utamaro were seen to have mica backgrounds.

Many of the finer "bijin-ga" prints of the later shin-hanga era also then used this technique with much effectiveness. Consider for example, many of the prints of the 1920's by both Goyo and Kotondo. This enhancing effect of a rich mica background is often seen in the printing of "bijin-ga" prints, where the artist or printer wants to impart an overall sumptuous effect.

Mica "sky" in c1890 Kunichika print. Mica background to c1920 Goyo "bijin-ga" image.

Visible Woodgrain

A final printing technique to be discussed in this brief article is the thoughtful and deliberate incorporation of visible woodgrain into the print's design. In Japanese, this technique is called "kimetsubushi," or "uniform grain printing." Such highly visible woodgraining is also one of the hallmarks of "early edition" prints, since "later editions" which are subsequently printed using the same blocks will often exhibit much less or no visible woodgraining as the pores of the woodblock's printing surface later become plugged and layered with pigments.

Here, it seems, praise must once again go to the carver, for perhaps he (or in combination with the printer) is responsible for this artistic use of the woodblock's natural and beautiful woodgrain. Such visible use and incorporation of the wood's natural woodgrain is certainly not just an accident. It seems very clear that even back to the days of Hiroshige's fine landscapes, careful thought was given to the selection of the single one or two woodblocks that would produce much of the large "un-carved surface background" to either the print's "sky" or "water" areas. The resulting effect is most delightful, and reminds us lest we should for a moment forget that these prints are indeed printed from wooden blocks.

Although less common to many of the prints of the early Meiji period (1870-80's), the deliberately artistic emphasis of visible woodgrain again became commonplace during the "War prints" of the mid-1890's, and then again to many of the finer shin hanga prints of the 1910's/20's/and 30's. Many fine examples can be seen from among the "kacho-e" (bird and flower) prints by Koson.

Woodgrain in a 1880's Kunisada print. Woodgrain in a c1910 Koson print.

Conclusion

Certainly all Japanese woodblocks are a beauty to behold, and we are profoundly blessed today with the priviledge of enjoying these fine works of art. However, what can especially stir the imagination and heart of the collector is the encounter with a print employing one or more of the deluxe printing techniques discussed above.

(c) Thomas Crossland and Andreas Grund, July 2002

Gallery

Terms

Ordering

About Us

We Buy Prints

Library